When Your Liver Shows Signs of More Than One Autoimmune Disease

Imagine your liver is under attack-not from a virus, not from alcohol, but from your own immune system. That’s what happens in autoimmune liver diseases. But sometimes, it’s not just one attacker. It’s two-or even three-working together. This is called an autoimmune overlap syndrome, and it’s more common than most people realize. Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC), Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC), and Autoimmune Hepatitis (AIH) can show signs of more than one condition at the same time. The result? Confusing blood tests, mixed-up biopsies, and treatment plans that don’t quite fit.

Most doctors are trained to look for one disease at a time. But when a patient has elevated liver enzymes, fatigue, and itching-plus antibodies that don’t match a single diagnosis-they might be dealing with an overlap. The most common of these is AIH-PBC. Studies show between 1% and 7% of people diagnosed with PBC also meet the criteria for AIH. In some groups, that number jumps to nearly 20%. PSC-PBC overlap, however, remains unproven. Despite rare case reports, experts agree there’s no solid evidence it exists as a true syndrome.

What Sets PBC, PSC, and AIH Apart-And How They Blend Together

Each of these diseases has a signature pattern. Think of them like fingerprints for the liver.

- AIH attacks liver cells directly. Blood tests show high ALT and AST-markers of liver cell damage. IgG levels rise, and you’ll often see ANA or SMA antibodies. A biopsy reveals interface hepatitis: immune cells creeping into the liver tissue like invaders breaking through a wall.

- PBC targets the small bile ducts inside the liver. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and GGT spike. The hallmark is anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA), found in 90-95% of cases. Biopsies show bile duct destruction and granulomas. IgM is usually elevated, not IgG.

- PSC affects larger bile ducts, both inside and outside the liver. ALP and GGT are high, but AMA is negative. The classic sign is a "beaded" appearance on MRCP scans-like a string of uneven beads along the ducts. It’s often linked to inflammatory bowel disease, especially ulcerative colitis.

Now, here’s where it gets messy. In AIH-PBC overlap, a patient might have high ALP and AMA (classic PBC), but also high ALT and IgG with ANA (classic AIH). The biopsy could show both bile duct damage and interface hepatitis. That’s not just one disease-it’s two wearing the same coat.

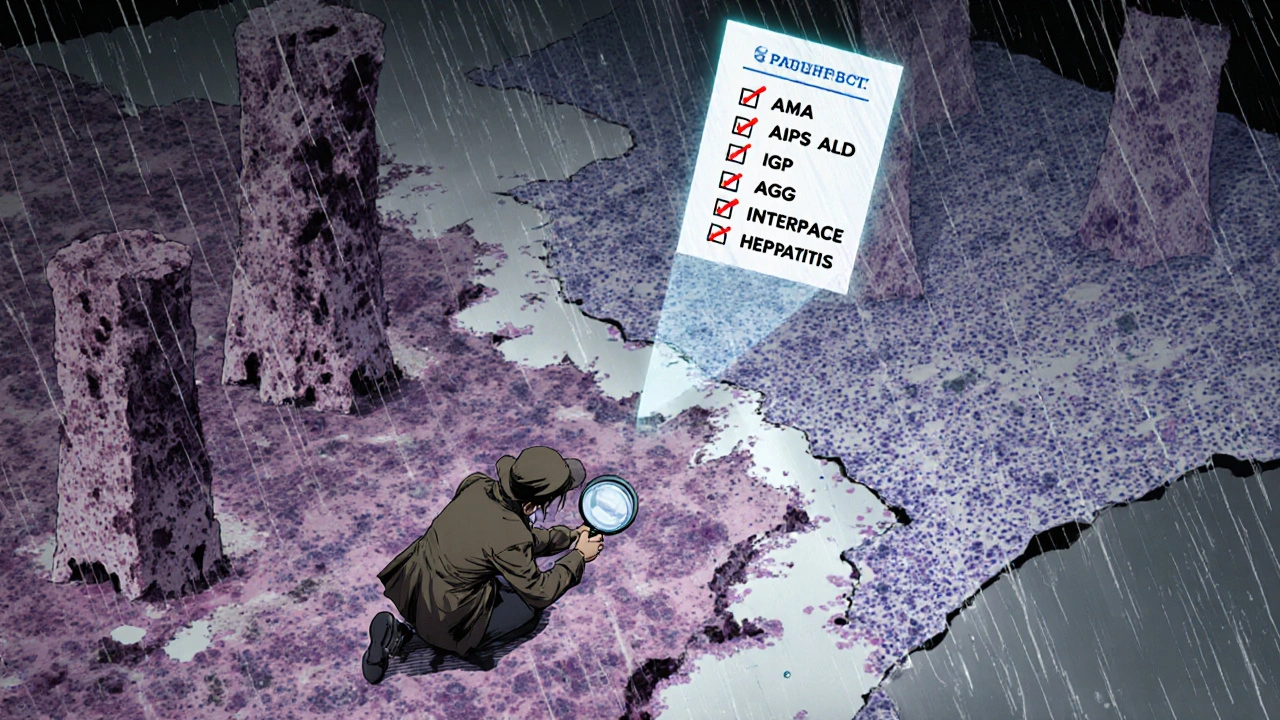

There’s no official checklist that says, "If you have X, Y, and Z, it’s an overlap." But most experts agree on this: if you meet two of the three diagnostic criteria for both PBC and AIH, you’re likely dealing with an overlap. For example: positive AMA + elevated ALP (PBC criteria) + elevated IgG + interface hepatitis (AIH criteria). That’s a red flag.

Why Diagnosis Is So Tricky-and Why It Matters

Getting this wrong can be dangerous. If a doctor sees high ALP and AMA and assumes it’s just PBC, they might start ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA). That’s the standard PBC treatment. But if the patient also has active AIH, UDCA alone won’t stop the liver inflammation. The ALT might stay high. Fatigue won’t improve. Fibrosis could keep creeping in.

Conversely, if a patient is misdiagnosed with AIH and given steroids and azathioprine, but they actually have PSC, those drugs won’t help-and could even cause harm. Steroids can mask symptoms without stopping bile duct damage in PSC. And in some cases, long-term immunosuppression increases infection risk without improving outcomes.

That’s why a full workup is non-negotiable. It’s not enough to check one antibody or one enzyme. You need:

- Comprehensive liver function tests (ALT, AST, ALP, GGT, bilirubin, albumin, INR)

- Autoantibody panel: AMA, ANA, SMA, anti-LKM1, sp100, gp210

- IgG and IgM levels

- MRCP or ERCP to check bile duct structure (especially if PSC is suspected)

- Liver biopsy-when results are unclear

One study found that 15-20% of overlap cases were missed in community clinics. These patients were treated for the wrong disease for months-or even years-before the real picture emerged. That delay can mean the difference between early intervention and irreversible cirrhosis.

Treatment: One Size Doesn’t Fit All

Standard treatment for PBC is UDCA. For AIH, it’s prednisone and azathioprine. But overlap syndromes? They need a hybrid approach.

Research shows that 30-40% of AIH-PBC patients don’t respond fully to UDCA alone. Their ALT levels stay elevated. Their fibrosis progresses. That’s when doctors add immunosuppressants. A 2020 case report followed a 39-year-old man with asymptomatic liver enzyme spikes for six years. He was diagnosed with PBC, but his IgG and ANA were high. After starting UDCA, his ALP dropped-but his ALT didn’t. Only after adding azathioprine did both normalize. He’s now in stable remission.

There’s no protocol that says, "Start with X, then add Y after Z weeks." Treatment is personalized. If AIH features dominate-high IgG, interface hepatitis-doctors lean toward steroids first. If PBC features are stronger-AMA-positive, cholestatic pattern-UDCA comes first, with immunosuppression added if needed.

And here’s something many don’t realize: even after starting treatment, these patients need lifelong monitoring. Their risk of cirrhosis is just as high as with single-disease forms. About 30-40% of untreated overlap cases develop cirrhosis within 10 years. Some go on to liver cancer. Regular ultrasounds and AFP blood tests are part of the routine.

The Controversy: Are Overlaps Real-or Just Variants?

Not every expert agrees that overlap syndromes are separate diseases. Some, like Dr. Keith Lindor from Mayo Clinic, argue they’re just extreme or unusual versions of one disease. Maybe AIH-PBC isn’t two diseases coexisting-it’s one disease with a broader immune attack pattern.

There’s some evidence for that. A 2022 review pointed out that PBC and AIH share many features: both affect women more than men, both cause fibrosis, both respond to immunosuppression in some way. The autoantibodies might not be as distinct as we thought. New markers like anti-sp100 and anti-gp210 are turning up in both PBC and AIH patients, blurring the lines even more.

Still, the clinical reality doesn’t change. Whether you call it an overlap or a variant, patients with mixed features behave differently. They need different treatment. They have different outcomes. And if you treat them like they have only one disease, you’re not treating them fully.

What’s Next for Autoimmune Liver Disease Research

The field is shifting. Instead of seeing PBC, PSC, and AIH as separate boxes, experts now think of them as points on a spectrum. Some patients sit firmly in one box. Others drift between them. The overlap syndromes are the gray zone in between.

Major groups like the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group are working on new diagnostic criteria-ones that will be validated in large, prospective studies. Early data from 2024 suggests these criteria will focus less on rigid checklists and more on patterns: which antibodies cluster together, which histological features appear side by side, how patients respond to different drugs.

One promising area is genetic profiling. Researchers are finding shared gene variants in patients with AIH-PBC overlap that aren’t seen in pure PBC or pure AIH. That could mean we’re not just seeing mixed symptoms-we’re seeing a distinct biological subtype.

For now, the best advice is simple: if your liver disease doesn’t fit neatly into one category, don’t force it. Look again. Test again. Talk to a specialist. The more you understand the full picture, the better your chances of stopping the damage before it’s too late.

Can you have PBC and PSC at the same time?

There’s no confirmed evidence that a true PBC-PSC overlap syndrome exists. While a few case reports describe patients with features of both, experts agree this is likely coincidental or misdiagnosed. PBC targets small bile ducts inside the liver and is marked by AMA positivity. PSC affects larger ducts and shows a beaded pattern on imaging. These are fundamentally different diseases with different causes. If someone has both sets of features, doctors usually suspect another condition-like drug injury or a rare genetic disorder-rather than a true overlap.

Is AIH-PBC overlap rare?

It’s not rare-it’s underdiagnosed. Studies show 1-3% of PBC patients and up to 7% of AIH patients have overlap features. In some research groups, the rate climbs to 9-19%. Because symptoms like fatigue and itching are common to both diseases, many patients go years without the full workup needed to spot the overlap. If you have PBC and your ALT stays high despite UDCA, or if you have AIH and your ALP is unusually high, an overlap should be suspected.

What’s the best test to confirm an overlap syndrome?

There’s no single test. Diagnosis requires combining blood work, imaging, and biopsy. Start with liver enzymes and autoantibodies: AMA for PBC, ANA/SMA/IgG for AIH. If results are mixed, an MRCP can rule out PSC. But the gold standard is a liver biopsy-it can show both bile duct damage (PBC) and interface hepatitis (AIH) in the same sample. Without a biopsy, you might miss the overlap entirely, especially if antibody levels are borderline.

Can you stop treatment if your blood tests improve?

No. Even if your ALT and ALP return to normal, stopping treatment can lead to rapid disease progression. Autoimmune overlap syndromes are chronic, lifelong conditions. The immune system doesn’t just "turn off" after symptoms improve. Most patients need to stay on UDCA indefinitely, and many require long-term immunosuppressants like azathioprine. Regular monitoring every 6-12 months is essential to catch early signs of relapse or liver damage.

Does having an overlap syndrome mean I’ll need a liver transplant sooner?

Not necessarily. The risk of cirrhosis is similar to that of single-disease forms-about 30-40% over 10 years if untreated. But with early diagnosis and proper combination therapy, many patients stabilize and never reach end-stage disease. Transplantation is still the last resort for those who do. Outcomes after transplant for overlap patients are generally good, though some studies suggest slightly higher rates of disease recurrence in the new liver. Close follow-up remains critical.

What to Do If You Suspect an Overlap

If you’ve been diagnosed with PBC, AIH, or PSC-but your symptoms don’t match your treatment response-it’s time to dig deeper. Ask your doctor for a full autoantibody panel. Request a liver biopsy if one hasn’t been done. Push for an MRCP if you have any signs of bile duct issues. Don’t accept a one-size-fits-all explanation. Your liver doesn’t care about labels. It responds to what’s actually happening inside it.

Early detection saves livers. And in autoimmune overlap syndromes, that means seeing the full picture-not just the part that fits the easiest diagnosis.

David Barry

November 11, 2025 AT 00:08Alex Ramos

November 11, 2025 AT 02:49Benjamin Stöffler

November 11, 2025 AT 03:09Mark Rutkowski

November 12, 2025 AT 16:30Chrisna Bronkhorst

November 14, 2025 AT 05:18Alyssa Lopez

November 14, 2025 AT 20:16edgar popa

November 16, 2025 AT 07:38Eve Miller

November 18, 2025 AT 05:19Amie Wilde

November 20, 2025 AT 03:54Ryan Everhart

November 20, 2025 AT 09:47Gary Hattis

November 21, 2025 AT 06:19