Drug-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis Risk Assessment Tool

How to Use This Tool

This tool assesses your risk of drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis based on your medication use and personal factors. It's not a substitute for medical advice. If you have concerns about your breathing, consult your doctor immediately.

Most people assume that if a doctor prescribes a medication, it’s safe. But some drugs don’t just treat illness-they quietly scar your lungs. Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis is one of the most dangerous, yet overlooked, side effects of common prescriptions. It doesn’t come with warning signs you can easily spot. No rash. No nausea. Just a dry cough that won’t go away, and breathlessness that creeps up slowly, like fog rolling in. By the time it’s diagnosed, the damage may already be permanent.

What Exactly Is Drug-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis?

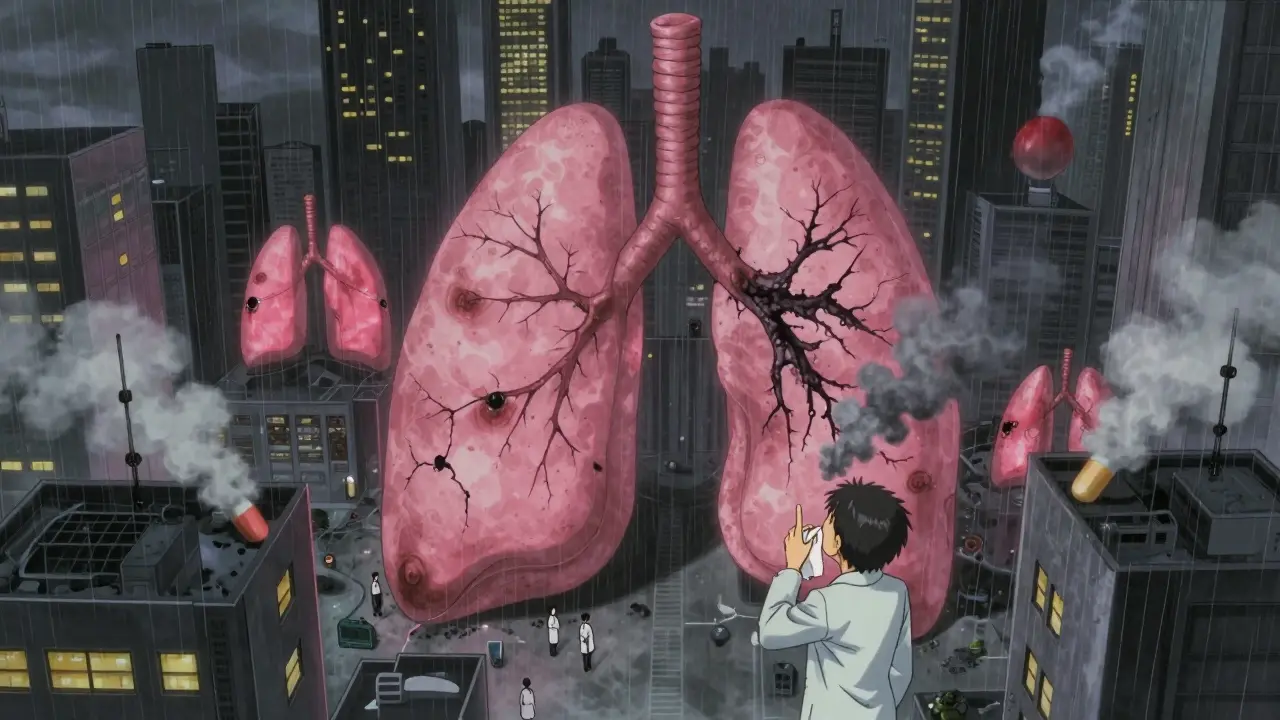

Pulmonary fibrosis means scar tissue builds up in your lungs. Normally, the walls around your air sacs are thin and flexible, letting oxygen pass easily into your blood. In fibrosis, those walls thicken, stiffen, and turn into scar tissue-like old rubber bands that lost their stretch. Your lungs can’t expand properly. You gasp for air even when you’re sitting still.

When this happens because of a medication, it’s called drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis (DIPF). It’s not common-but it’s real, and it’s getting more frequent. Studies show it makes up 5-10% of all interstitial lung diseases. And unlike infections or autoimmune conditions, DIPF is directly tied to the drugs you take. The scary part? It can happen to anyone. One person takes the same pill for years and feels fine. Another develops life-threatening scarring after just a few months. No one knows why.

The Top Medications That Cause Lung Scarring

Over 50 drugs have been linked to pulmonary fibrosis. But a handful stand out because they’re widely prescribed-and their risks are poorly understood.

- Nitrofurantoin: Used for urinary tract infections, especially in older adults. Long-term use-even just six months-can trigger lung damage. Cases show up years after starting the drug. In New Zealand, it was the #1 reported cause of medication-related lung scarring between 2014 and 2024.

- Methotrexate: A go-to for rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. It’s cheap, effective, and often taken for decades. But 1-7% of users develop lung inflammation that turns into fibrosis. Many patients blame their cough on aging or allergies until it’s too late.

- Amiodarone: A heart rhythm drug prescribed to millions. After taking more than 400 grams total (about 6-12 months of daily use), up to 7% of patients develop lung scarring. It’s slow to show up, so doctors rarely connect the dots.

- Bleomycin: A chemotherapy drug. Up to 20% of patients on high doses get severe lung injury. It’s one of the most dangerous drugs for the lungs in oncology.

- Cyclophosphamide: Another chemo agent. Around 3-5% of users develop fibrosis. Often, patients don’t realize their worsening breathlessness is from the drug, not the cancer.

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Newer cancer drugs like pembrolizumab and nivolumab. Since 2011, they’ve been linked to sudden, aggressive lung inflammation. Some patients develop fibrosis within weeks of starting treatment.

The pattern? These aren’t rare or experimental drugs. They’re standard, everyday prescriptions. And their lung risks are buried in fine print.

Why Is It So Hard to Diagnose?

There’s no single test for drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Chest X-rays might look normal. Blood tests don’t pick it up. Even CT scans can’t tell if the scarring came from a drug or something else-like asbestos, radiation, or an autoimmune disease.

Doctors rely on one key clue: your medication history. If you’ve been on nitrofurantoin for five years and suddenly can’t climb stairs without stopping, the link should be obvious. But in practice, it rarely is. A 2022 survey found only 58% of primary care doctors routinely ask patients about breathing problems when they’re on high-risk drugs.

Patients often delay seeking help. They think, “I’m getting older,” or “I’m just out of shape.” One Reddit user wrote: “I went to three doctors before someone asked what meds I was on. By then, I’d lost 30% of my lung function.” The average time from first cough to correct diagnosis? Over eight weeks.

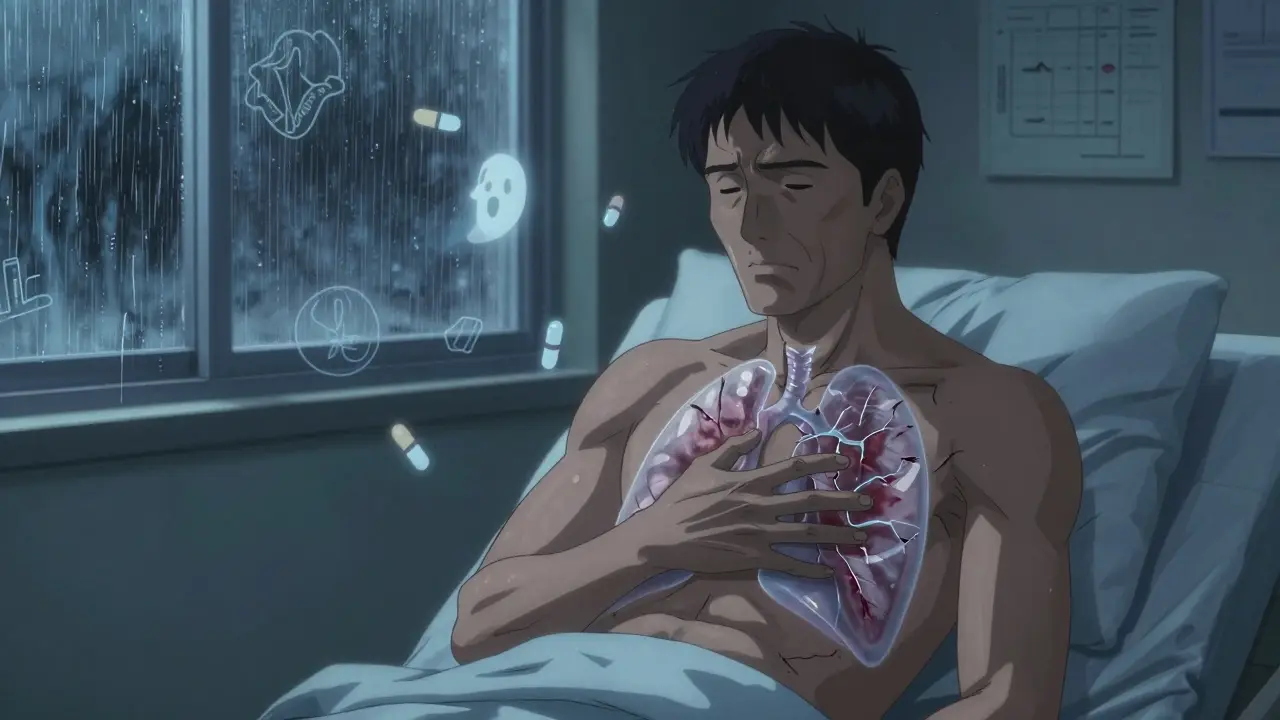

What Happens If You Don’t Stop the Drug?

Stopping the drug is the single most effective treatment. In 89% of cases, lung function improves within three months of quitting the culprit medication. But if you keep taking it? The scarring keeps growing. And once scar tissue forms, it doesn’t go away.

Some people recover almost fully. Others are left with permanent damage-needing oxygen tanks, pulmonary rehab, or even a lung transplant. Mortality rates for severe cases range from 10% to 20%. In New Zealand, 30 people died from drug-induced lung scarring between 2014 and 2024. Most were on nitrofurantoin, methotrexate, or amiodarone.

Doctors often turn to steroids like prednisone to calm the inflammation. But steroids don’t reverse scar tissue. They just slow the damage. Oxygen therapy helps with symptoms. But the only real fix? Get off the drug before the lungs turn to stone.

Who’s at Risk?

Age matters. Most cases occur in people over 60. But it’s not just about being old. Long-term use is the biggest risk factor. Someone on amiodarone for heart failure for three years has a much higher chance than someone who took it for two weeks.

Women appear to be slightly more vulnerable to methotrexate-related lung damage. Smokers have worse outcomes. And people with pre-existing lung conditions-like asthma or COPD-are at higher risk of rapid decline.

The biggest risk factor, though, is ignorance. If you don’t know your medication can scar your lungs, you won’t notice the warning signs. And if your doctor doesn’t ask, you won’t think to tell them.

What Should You Do?

If you’re taking any of these drugs, pay attention to your body.

- Is your cough dry and persistent?

- Do you get out of breath faster than before-walking to the mailbox, climbing stairs, even talking?

- Do you feel tired all the time, or have unexplained fevers?

If you answer yes to any of these, talk to your doctor. Don’t wait. Bring a list of every medication you take-prescription, over-the-counter, even supplements. Ask: “Could any of these be affecting my lungs?”

Ask for a pulmonary function test. It’s simple. You breathe into a tube. It measures how much air your lungs can hold and how well oxygen moves into your blood. Do it once a year if you’re on long-term high-risk meds.

And if your doctor dismisses your concerns? Get a second opinion. Pulmonary fibrosis from drugs is treatable-if caught early. But it’s deadly if ignored.

The Bigger Picture

Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis isn’t going away. New drugs are approved every year. Many have unknown long-term effects. The number of reported cases has risen 23.7% in the last decade. Regulatory agencies like New Zealand’s Medsafe are now warning doctors to be more vigilant.

But awareness still lags. Patients aren’t told. Doctors aren’t trained. The system is built to treat symptoms, not prevent hidden damage.

The truth? Medicine saves lives-but it can also silently destroy them. The best defense? Know your drugs. Know your body. And never ignore a cough that won’t quit.

josh plum

January 5, 2026 AT 05:39John Ross

January 6, 2026 AT 09:02Clint Moser

January 7, 2026 AT 01:47Ashley Viñas

January 8, 2026 AT 01:24Mandy Kowitz

January 9, 2026 AT 05:25Oluwapelumi Yakubu

January 9, 2026 AT 10:36Jacob Milano

January 11, 2026 AT 05:00Enrique González

January 12, 2026 AT 19:11Aaron Mercado

January 14, 2026 AT 09:19saurabh singh

January 15, 2026 AT 20:14Dee Humprey

January 16, 2026 AT 13:47John Wilmerding

January 16, 2026 AT 20:50Peyton Feuer

January 18, 2026 AT 02:59Connor Hale

January 19, 2026 AT 11:23