When you see a headline like "New Study Links Blood Pressure Drug to 50% Higher Risk of Stroke," it’s natural to panic. You might even consider skipping your next dose. But before you do, stop and ask: Is this report accurate? Most media stories about medication safety don’t tell the full story-and many get it dangerously wrong.

What’s Really Being Reported?

Not every bad outcome after taking a drug is caused by the drug. There’s a big difference between an adverse drug reaction (an expected side effect) and a medication error (a preventable mistake like the wrong dose or wrong patient). Media reports often blur these lines. A 2021 study in JAMA Network Open found that 68% of news articles didn’t even say which type of event they were talking about. That’s like reporting a car crash without saying if it was caused by a broken brake or a driver texting. Look for clear language. If the article says "linked to," "associated with," or "may increase risk," that’s a red flag. Those phrases mean the study found a correlation-not proof of cause. Real science reports absolute risk (how many people out of 100 actually had the problem) and relative risk (how much higher the chance is compared to others). For example, if a drug raises your stroke risk from 2 in 1,000 to 3 in 1,000, that’s a 50% relative increase-but only a 0.1% absolute increase. That’s not the same as saying "half of people will have a stroke." Yet, 79% of media reports leave out the absolute numbers.Where Did the Data Come From?

Medication safety data doesn’t come from magic. It comes from real studies. The most common methods are:- Incident reports (voluntary reports from doctors or patients)-these miss most events because people don’t report them.

- Chart reviews (doctors going back through medical records)-these catch only 5-10% of actual errors, according to Dr. David Bates, who helped develop this method.

- Trigger tools (using specific warning signs in records to flag possible problems)-this is the most efficient method and finds the most relevant issues.

- Direct observation (watching nurses or pharmacists at work)-accurate but expensive and rare.

Are They Using the Right Data Sources?

You’ll often see media cite the FDA’s FAERS database (Adverse Event Reporting System) or the WHO’s global database. But here’s the catch: these systems collect reports, not confirmed causes. If someone takes a drug and then has a heart attack two weeks later, they or their doctor might report it. But that doesn’t mean the drug caused it. The person could have been at high risk already. In fact, studies show 90-95% of actual medication errors are never reported. A 2021 study in Drug Safety found that only 44% of media reports explained this critical difference. That means most readers think every report in FAERS is a confirmed danger. It’s not. It’s a starting point for investigation-not proof of harm.

Did They Check for Bias?

Good studies control for things like age, other medications, smoking, or pre-existing conditions. These are called confounding factors. If a study says a drug increases heart attack risk, but didn’t account for the fact that users were older and sicker to begin with, the result is misleading. The FDA’s 2022 guidelines say any serious safety study must show it controlled for these factors. Yet, a 2021 audit in JAMA Internal Medicine found only 35% of media reports mentioned this at all. That’s like saying a new diet caused weight loss without mentioning that everyone on the diet also started walking 10,000 steps a day.Who’s Saying This-and Why?

Not all sources are equal. A 2020 BMJ study compared how different media handled medication safety news:- Major newspapers (NYT, Guardian): 62% correctly explained absolute vs. relative risk

- Cable news: 38%

- Digital-only outlets: 22%

What About Social Media?

Instagram and TikTok are the worst offenders. A 2023 analysis by the National Patient Safety Foundation found 68% of medication safety claims on those platforms were false. One viral video claimed a common diabetes drug caused "permanent nerve damage"-but the original study used doses 15 times higher than what people take. No one mentioned that. Thousands of people stopped their meds because of it. A 2023 Kaiser Family Foundation survey found 61% of U.S. adults changed their medication habits after reading a news report. 28% stopped taking their prescriptions entirely. That’s not just misinformation-it’s dangerous.

How to Check It Yourself

Here’s a simple 5-step checklist to use every time you read a medication safety story:- Is it a medication error or an adverse reaction? Look for the distinction. If it’s missing, be skeptical.

- What’s the absolute risk? If they only give you a percentage increase (like "50% higher risk"), demand the baseline. What’s the real chance?

- What study method was used? Was it chart review? Trigger tool? Spontaneous report? Each has limits.

- Did they control for other factors? Age? Other drugs? Health status? If not, the result is probably misleading.

- Can you find the original source? Go to clinicaltrials.gov or the FDA’s FAERS database. See what the real study says. Don’t trust the summary.

What Should You Do?

Don’t stop your meds because of a headline. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist. They know your history. They know your risks. They know the difference between a real signal and noise. If you’re worried about a drug you’re taking, check the Medication Guide that comes with your prescription. It’s written by the FDA and lists real risks with real numbers. You can also look up your drug on the FDA website or the WHO’s ATC classification system to confirm what class it’s in. Misclassification is common-47% of media reports get it wrong. And if you see a terrible report? Share the facts. Link to the original study. Tell your friends why the headline is misleading. Misinformation spreads fast. Accurate information needs to catch up.What’s Changing?

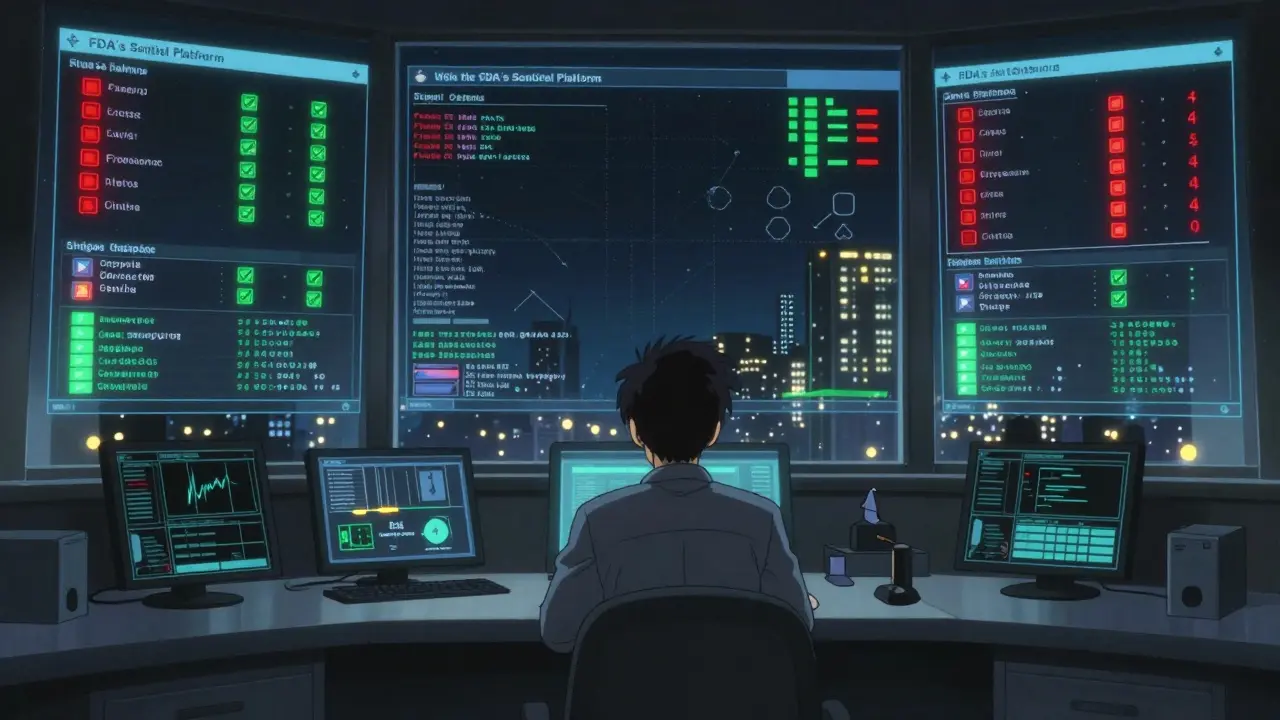

Good news: tools are getting better. The FDA’s Sentinel Analytics Platform now uses real-world data from millions of patients to spot true safety signals. It’s not perfect, but it’s far more reliable than spontaneous reports. Only 18% of reporters use it right now-but that’s changing. The WHO is pushing for global standardization of error reporting. Right now, only 19.6% of countries use fully standardized systems. When that changes, media reports will have better data to work with. In the meantime, your best tool is your brain. Question everything. Demand context. Look for numbers, not just fear.Medication safety isn’t about avoiding all risk. It’s about understanding real risk-and not letting fear make decisions for you.

Alex Warden

January 1, 2026 AT 22:08This media crap is why America's falling apart. They scare you with 50% higher risk and don't tell you it's from 2 in 1000 to 3 in 1000. That's like saying a raindrop will flood your house. Who writes this stuff? I'm sick of it.

My grandma took this drug for 10 years and never had a stroke. But the news says it's deadly? Nah. They just want you to click and panic. Fake outrage sells.

Stop listening to TV. Go read the actual study. Or better yet, talk to your pharmacist. They don't give a damn about clicks.

Lee M

January 2, 2026 AT 21:54Reality is a construct shaped by language. When media says 'linked to,' they're not reporting facts-they're constructing a narrative of fear. The absolute risk is the only ontological truth here. The relative risk is a linguistic trick, a Hegelian inversion of meaning.

Our society has outsourced critical thinking to algorithms and headlines. We've become consumers of emotional data, not seekers of epistemic clarity. The drug isn't the problem. The epistemological collapse is.

True freedom isn't taking pills. It's refusing to be manipulated by statistical theater.

Kristen Russell

January 3, 2026 AT 19:31Love this breakdown. So many people panic and quit meds because of scary headlines. But if you just pause and check the numbers, most of it’s not even close to what it sounds like.

My dad was scared to take his blood pressure med after a viral TikTok. We looked up the FDA data together. His actual risk went from 0.2% to 0.3%. He kept taking it. Still here at 78.

Knowledge > fear. Always.

sharad vyas

January 4, 2026 AT 13:07In my country, we do not rush to judge a medicine by a headline. We wait. We ask. We respect the wisdom of doctors and elders.

Media wants noise. We want peace. Science is not for shouting. It is for listening.

Thank you for writing this. It reminds me of my grandfather who said, 'If your mind is loud, your soul is quiet.'

Let us be quiet. Let us learn.

Dusty Weeks

January 5, 2026 AT 12:21bro i saw a post on reddit that said this drug causes your tongue to turn purple and you die in 3 days 😭

i almost stopped mine... then i found the original study and it was like... 'we gave 15x the normal dose to rats'

why is the internet like this?? 🤡

also i cried reading this. thank you. 🙏

Richard Thomas

January 6, 2026 AT 19:17It’s interesting how deeply we’ve internalized the idea that risk must be dramatic to be real. We’ve been trained to equate magnitude of fear with magnitude of truth. But the truth is often quiet-statistical, incremental, buried under layers of methodology and context.

What’s lost here isn’t just accuracy-it’s trust. Trust in science, in medicine, in institutions. And when that erodes, people don’t just stop taking pills. They stop trusting anyone who tries to help them.

I’ve seen patients abandon life-saving treatments because of a single misleading headline. Not because they’re irrational. Because they’ve been lied to so many times, they’ve learned to distrust all signals-even the good ones.

We need more than checklists. We need cultural repair. We need media that treats people like thinking beings, not targets.

And we need to stop rewarding outrage with clicks.

Paul Ong

January 8, 2026 AT 10:47Just talk to your doctor

Check the med guide

Don't trust the news

Go to FDA website

Simple

Done

Stop overthinking

You got this

Andy Heinlein

January 9, 2026 AT 01:43Man I used to be one of those people who’d quit meds over headlines. Then my sister had a stroke and they found out she was on a drug that actually helped her-except the news said it was dangerous.

Turns out she was in the 0.1%. But the headline made it sound like everyone was doomed.

I now share this post every time I see a scary med story. Just to remind people: numbers don’t lie. Fear does.

Also side note-TikTok is a horror movie with dance music.

Stay calm. Stay informed. You’re not alone.

Austin Mac-Anabraba

January 11, 2026 AT 01:12Let’s be clear: this isn’t about media literacy. It’s about systemic deception. The pharmaceutical industry funds 80% of clinical trials. The FDA’s FAERS database is a garbage fire of unverified anecdotes. The media doesn’t misreport-they’re complicit.

When you see a headline like '50% higher risk,' you’re not reading journalism. You’re reading a marketing funnel designed to sell ads, drive fear-based subscriptions, and create panic-driven compliance.

And the people who benefit? The ones who profit from your anxiety. The ones who sell you supplements to 'counteract the side effects' of drugs you were never supposed to stop.

This isn’t ignorance. It’s exploitation. And until we treat it like a public health crisis, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Phoebe McKenzie

January 12, 2026 AT 01:06HOW DARE YOU. You think this is just about numbers? This is about LIVES. People are DYING because of this garbage reporting. My cousin died because she stopped her med after a viral post. She was 32. She had a baby.

And you want me to 'check the original study'? Do you know how many people can’t read a clinical trial? Do you know how many don’t have internet? How many are elderly? How many are scared?

This isn’t a logic puzzle. It’s a moral failure. And the media? They’re not just lazy-they’re evil.

Stop pretending this is about 'critical thinking.' It’s about accountability. And someone needs to go to jail for this.