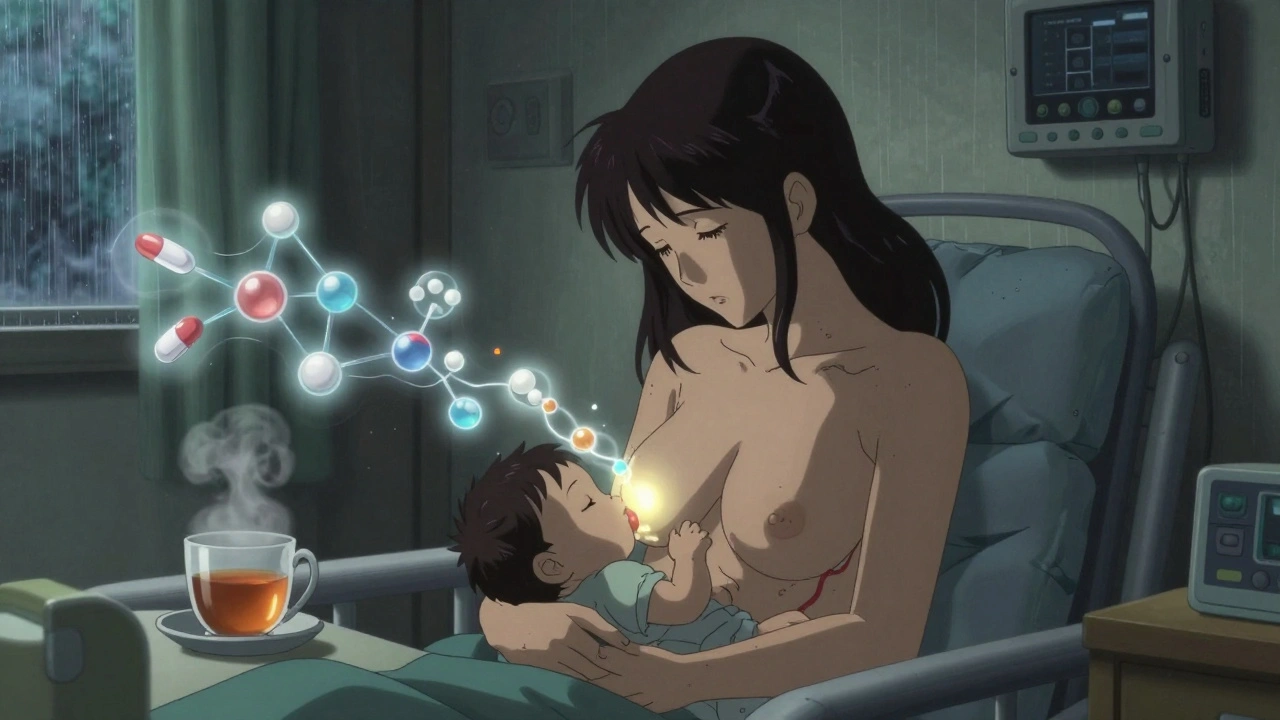

When you’re breastfeeding and need to take a medication, it’s natural to worry: is this safe for my baby? You’re not alone. More than half of all breastfeeding mothers take at least one medication - whether it’s for pain, an infection, anxiety, or a chronic condition. The good news? Over 98% of these medications are safe. The challenge isn’t finding dangerous drugs - it’s knowing which ones are truly safe, and why.

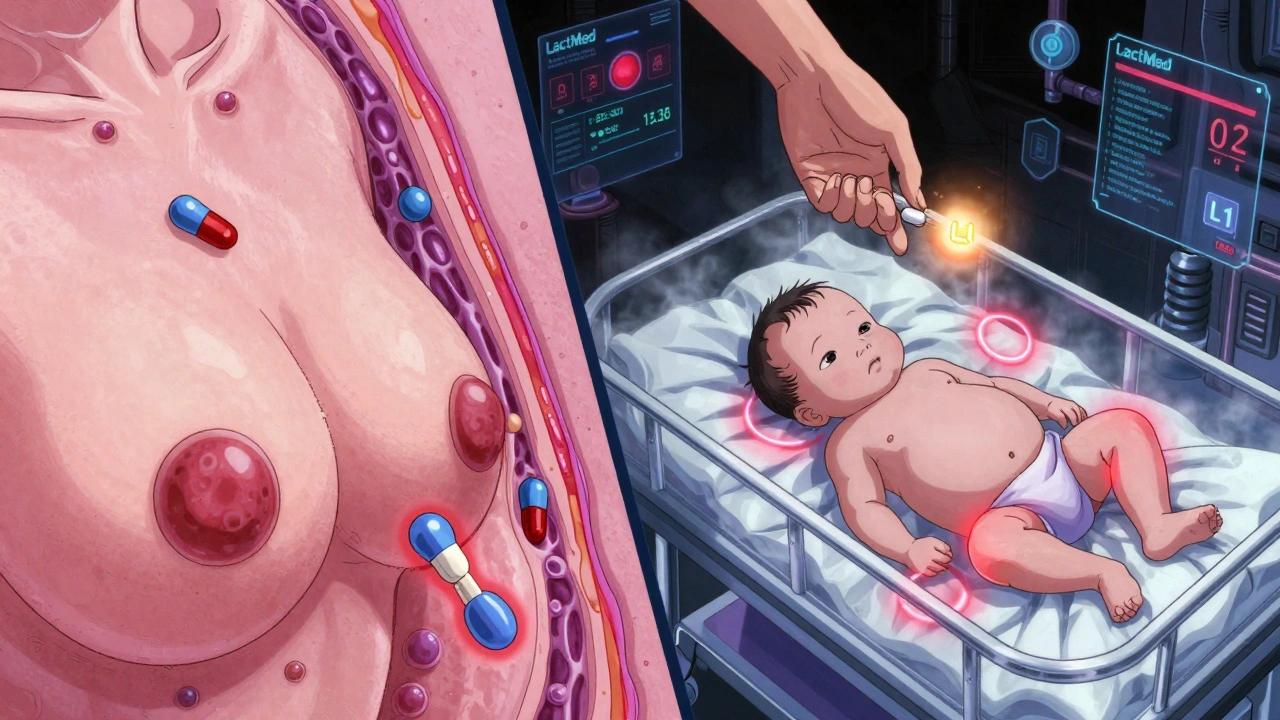

How Medications Get Into Breast Milk

Medications don’t magically appear in breast milk. They travel from your bloodstream into your milk through a simple physical process called passive diffusion. Think of it like a sponge soaking up water. The drug moves from where it’s more concentrated (your blood) to where it’s less concentrated (your milk). But not all drugs do this equally. Four key factors determine how much of a drug ends up in your milk:- Molecular weight: Smaller molecules (under 200 daltons) slip through easily. Most common drugs - like ibuprofen or amoxicillin - are tiny enough to pass.

- Lipid solubility: Fatty drugs cross membranes better. Drugs like antidepressants or benzodiazepines can have higher milk levels because they dissolve in fat.

- Protein binding: If a drug sticks tightly to proteins in your blood (over 90%), it can’t get into milk. Warfarin and most SSRIs are highly bound, so very little reaches your baby.

- Half-life: Drugs that stay in your system longer (over 24 hours) have more time to build up in milk. Shorter half-life drugs like acetaminophen clear out fast.

There’s also something called ion trapping. Breast milk is slightly more acidic than your blood. Weakly basic drugs - like some antidepressants or lithium - get "trapped" in milk and can reach concentrations two to ten times higher than in your blood. That doesn’t mean they’re dangerous, but it does mean you need to pay attention.

Right after birth, your milk is colostrum - thick, sticky, and low in volume. The gaps between milk-producing cells are wider, so drugs can get in more easily. But here’s the catch: your baby is only drinking 30-60 mL a day. By day five, your milk volume jumps to 500-800 mL, but those gaps close up. So early exposure is real, but the total amount your baby gets is still tiny.

The L1 to L5 Risk Scale: What Doctors Actually Use

You’ve probably heard conflicting advice about breastfeeding and meds. One doctor says it’s fine. Another says to stop. The confusion comes from outdated guidelines or guesswork. The gold standard? Dr. Thomas Hale’s L1-L5 classification system, now used worldwide.- L1 - Safest: No documented risk. Examples: ibuprofen, acetaminophen, penicillin, levothyroxine.

- L2 - Probably Safe: Limited data, but no adverse effects reported. Examples: sertraline, citalopram, amoxicillin-clavulanate.

- L3 - Possibly Safe: No controlled studies in humans. Risk can’t be ruled out. Examples: fluoxetine, lithium, tramadol.

- L4 - Possibly Hazardous: Evidence of risk, but benefits may outweigh risks. Examples: diazepam (if used occasionally), cyclosporine.

- L5 - Contraindicated: Clear risk. Avoid. Examples: chemotherapy drugs, radioactive isotopes, ergotamine.

Here’s what matters: most medications are L1 or L2. The American Academy of Pediatrics says over 95% of drugs are compatible with breastfeeding. Only about 1% require stopping nursing - and even then, it’s often temporary.

Top Medications You’re Likely Taking - And What the Data Says

Let’s cut through the noise. These are the drugs most breastfeeding mothers use - and what we know about them.Analgesics (Pain Relievers)

- Acetaminophen: Less than 1% of the maternal dose reaches milk. Safe at standard doses.

- Ibuprofen: Very low transfer. Even high doses (800 mg) show no effect on infants. Preferred over naproxen.

- Tramadol: L3. Can cause drowsiness in newborns. Use only if no alternatives. Avoid if baby is premature or has breathing issues.

Antibiotics

- Amoxicillin: L1. Safe. May cause mild diaper rash or fussiness - not an allergy.

- Cephalexin: L1. No adverse effects reported.

- Metronidazole: L2. Used to be avoided, but now considered safe. Take a single 2g dose after a feeding. Wait 12-24 hours if worried.

- Tetracycline: L2. Avoid long-term use in infants under 8 - but short courses (5-7 days) are fine for moms.

Psychotropics (Antidepressants, Anti-Anxiety)

- Sertraline: L1. Lowest transfer of all SSRIs. Most studied. Often first choice.

- Citalopram: L2. Safe, but higher doses (>40 mg) may cause irritability in infants.

- Fluoxetine: L3. Long half-life. Can build up in baby’s system. Avoid if baby is newborn or preterm.

- Benzodiazepines (e.g., lorazepam): L2. Use short-term and low dose. Avoid long-acting ones like diazepam.

Thyroid, Blood Pressure, and Diabetes Meds

- Levothyroxine: L1. Safe. Your body needs it - even more now.

- Lisinopril: L2. Low transfer. Safe.

- Metformin: L1. Very low milk levels. No effect on infant blood sugar.

Bottom line: If a drug is safe for your baby to take directly (like infant acetaminophen), it’s almost always safe through breast milk. The dose your baby gets is tiny - often less than 1% of what you take.

When Timing Matters: How to Reduce Exposure

You don’t have to stop breastfeeding to stay healthy. You just need to time things right.- Take meds right after breastfeeding: This gives your body time to clear the drug before the next feeding. If you take a pill at 10 PM, your baby’s next feed might be at 3 AM - giving you 5 hours of clearance.

- Use the shortest half-life option: Choose ibuprofen over naproxen. Sertraline over fluoxetine.

- For multiple daily doses: Take the dose right before the longest stretch of sleep. That’s usually at night.

- Avoid long-acting or extended-release pills: They keep drug levels steady for hours - meaning more exposure over time.

- Topical meds are safer: Creams, patches, eye drops. Just don’t apply them to your nipple unless you wipe them off before feeding.

One study found that mothers who timed their doses this way reduced infant exposure by up to 80% - without changing their medication.

Reliable Resources - Not Google

Google searches give you fear-based blogs and outdated advice. You need science-backed, real-time data.- LactMed (NIH): Free, updated daily, covers 4,000+ drugs and 350 herbs. Used by over 1.2 million people yearly. Best for detailed pharmacokinetics.

- InfantRisk Center: Offers quick L1-L5 ratings and phone consultations. Their MilkLab study has measured actual drug levels in breast milk for over 200 medications.

- Medications and Mothers’ Milk by Dr. Thomas Hale: The go-to clinical guide. Updated every two years. More user-friendly than LactMed.

- MotherToBaby: Free hotline (1-866-626-6847) staffed by specialists. Handles 15,000 calls a year.

Don’t rely on apps like WebMD or pregnancy forums. They often list drugs as "unsafe" based on theory, not real-world data.

What to Watch For in Your Baby

Most babies show no signs at all. But if you notice any of these, talk to your doctor:- Unusual sleepiness or difficulty waking to feed

- Poor feeding or vomiting

- Unusual fussiness or irritability

- Rash or diarrhea (especially after starting antibiotics)

These are rare. Less than 2% of breastfed infants have any clinically significant reaction. And in most cases, the reaction stops when you stop the drug.

What You Should Never Do

- Stop breastfeeding without checking a reliable source. 78% of lactation consultants report mothers being wrongly told to quit nursing over medication.

- Switch to formula because you’re "afraid" of meds. The benefits of breastfeeding far outweigh the risks of nearly all medications.

- Use herbal supplements without checking. LactMed now includes 350 herbs. Many - like sage, peppermint, or goldenseal - can reduce milk supply.

- Assume "natural" means safe. Some herbal teas contain stimulants or toxins that transfer easily.

The Future: Personalized Lactation Pharmacology

Right now, we guess based on averages. But by 2030, that’s changing. Researchers are already testing how your genes affect how you process drugs. One study found that women with certain liver enzyme variants clear sertraline faster - meaning less ends up in milk.The FDA now encourages drug companies to include breastfeeding women in trials. Right now, only 12 of 85 FDA-approved biologics (like Humira or Enbrel) have breastfeeding data. That’s changing.

Soon, you might get a personalized report: "Based on your genetics, your infant will receive 0.3% of your dose of fluoxetine - well below the safety threshold." That’s not science fiction. It’s coming.

Final Takeaway

You don’t have to choose between being a healthy mom and a breastfeeding mom. You can be both. Most medications are safe. Most babies are fine. The key is knowing which ones are safe - and how to use them wisely.Don’t guess. Don’t panic. Don’t stop nursing because someone told you to. Check LactMed. Talk to your doctor. Time your doses. And keep feeding - because what you’re giving your baby isn’t just milk. It’s protection, immunity, and love - all of which matter more than the tiny amount of medicine that might come with it.

Can I take ibuprofen while breastfeeding?

Yes. Ibuprofen is classified as L1 - the safest category. Less than 0.1% of your dose transfers into breast milk. It’s even safer than acetaminophen for some mothers because it doesn’t affect the liver. No adverse effects have been reported in breastfed infants at standard doses.

Is it safe to take antidepressants while breastfeeding?

Yes, most are. Sertraline and citalopram are the most studied and safest. Sertraline transfers at less than 1% of the maternal dose and has no reported side effects in infants. Fluoxetine is less ideal because it stays in the system longer and can build up. Never stop antidepressants abruptly - untreated depression is far riskier for both you and your baby than the medication.

What if my baby is premature or has health issues?

Premature or sick infants process drugs slower. Their liver and kidneys aren’t fully developed. For these babies, even low-risk drugs need extra caution. Avoid drugs with long half-lives (like fluoxetine or diazepam). Use the lowest effective dose. Always consult a lactation specialist or pediatrician. Many hospitals have specialized clinics for this exact situation.

Do herbal teas or supplements affect breast milk?

Yes. Many are unregulated and can transfer into milk. Sage, peppermint, and parsley can reduce milk supply. Chamomile and valerian may cause drowsiness in infants. LactMed lists over 350 herbs with safety ratings. Never assume "natural" means safe. Always check before using.

Should I pump and dump after taking medication?

Almost never. Pumping and dumping doesn’t speed up drug clearance - your body removes it from your blood naturally. The only exceptions are for drugs with very high toxicity (like chemotherapy or radioactive iodine) or if you took a one-time high dose (like a strong painkiller after surgery). For routine medications, it’s unnecessary and can hurt your supply.

How do I know if my baby is reacting to my medication?

Watch for changes: unusual sleepiness, trouble feeding, excessive fussiness, or rash. These are rare. If you notice them, note the timing - did they start after you began the new medication? Talk to your pediatrician. In most cases, stopping the drug for 2-3 days will tell you if it’s the cause. Never stop a necessary medication without medical advice.

Jamie Clark

December 14, 2025 AT 03:59Let’s be real-this whole ‘98% safe’ narrative is corporate propaganda dressed up as science. You think they’d publish data on every drug that’s ever been tested? Half the L1-L5 scale is based on animal studies and extrapolation. The FDA doesn’t test on lactating women because it’s too risky for their liability. So yeah, ‘safe’ means ‘not proven dangerous yet’-big difference. I’d rather err on the side of caution than let my kid become a guinea pig for Big Pharma’s convenience.

Keasha Trawick

December 14, 2025 AT 19:45Okay, but let’s talk pharmacokinetics for a sec-this is *fascinating*. Passive diffusion, ion trapping, protein binding thresholds-it’s like your milk is a selective bouncer at a VIP club, letting in the small, lipophilic VIPs while kicking out the bulky, protein-bound gatecrashers. And the fact that colostrum has wider paracellular gaps? That’s not just biology, that’s evolutionary engineering. Your body knows the newborn’s liver can’t handle much, so it limits early exposure. Then, when the baby’s system matures? Boom-milk volume ramps up, gaps seal, and you’re delivering therapeutic-grade nutrients, not toxins. This isn’t medicine. This is magic. And I’m here for it.

Bruno Janssen

December 16, 2025 AT 12:22I took sertraline for 18 months while nursing. My kid never slept. Never. Just stared at the wall like he was processing quantum physics. I didn’t know it was the meds until I weaned him. Then he slept 7 hours. Coincidence? Maybe. But I’ll never trust another L1 rating again.

Emma Sbarge

December 18, 2025 AT 12:11Stop being so dramatic. This isn’t a horror movie. If you can’t trust science, you shouldn’t be a parent. The AAP says 95% of meds are compatible. LactMed is run by the NIH. Your kid isn’t getting poisoned by ibuprofen. You’re just scared because you don’t understand pharmacology. Get educated or get out of the breastfeeding club.

Deborah Andrich

December 19, 2025 AT 23:35I’m a nurse and I’ve seen moms panic over meds they don’t need to worry about. I’ve also seen moms ignore red flags because they didn’t want to admit they needed help. The truth is somewhere in the middle. Listen to your gut but also listen to LactMed. If your baby is unusually sleepy or not gaining weight, don’t wait. Talk to someone. You’re not failing if you pause nursing for 48 hours to test a theory. You’re being responsible. And if you’re taking meds for depression? You’re already doing the hardest thing in parenting. Be kind to yourself.

Richard Ayres

December 21, 2025 AT 04:24Thank you for this comprehensive breakdown. The L1-L5 system is underutilized in primary care, and many OB-GYNs still rely on outdated guidelines. I appreciate the emphasis on timing-taking medication post-feed is a simple, effective strategy that’s often overlooked. The data on topical agents and the warning against herbal supplements are particularly valuable. This is the kind of evidence-based guidance that should be distributed to every new parent.

Sheldon Bird

December 23, 2025 AT 03:09YOU GOT THIS. Seriously. I was terrified when I started antidepressants after my second. But I followed the timing, used sertraline, checked LactMed daily, and my kid is now a thriving 3-year-old who doesn’t even know what a pill is. You’re not hurting your baby-you’re giving them the best gift: a healthy, present mom. Pump and dump? Nah. Just time it right and keep going. You’re stronger than you think 💪🍼

Karen Mccullouch

December 23, 2025 AT 03:59My mom told me to stop breastfeeding when I took antibiotics. She said ‘natural is better.’ Guess what? My kid got ear infections three times that year. I switched to formula and he cried nonstop. Then I went back to breastfeeding with amoxicillin-no issues. Stop listening to grandmas and Google. Science wins. And if you’re too scared to take meds? Then maybe you’re not ready for motherhood.