When you hear "MRSA," you might think of a hospital-acquired infection - something that happens to sick, hospitalized patients. But that’s not the whole story anymore. Since the late 1990s, a new kind of MRSA has been spreading in gyms, locker rooms, prisons, and even homes - among people who’ve never set foot in a hospital. This isn’t just a hospital problem. It’s a community problem. And the two are now feeding each other.

What Exactly Is MRSA?

MRSA stands for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. It’s a type of staph bacteria that doesn’t respond to common antibiotics like methicillin, penicillin, or amoxicillin. Staph bacteria are everywhere - on skin, in noses, in throats. Most of the time, they’re harmless. But when they get into a cut, scrape, or wound, they can cause infections. MRSA makes those infections harder to treat because the usual drugs don’t work.

For decades, MRSA was mostly seen in hospitals. It showed up in patients after surgery, on catheters, or in intensive care units. But then something changed. Healthy people - athletes, kids, military recruits, prison inmates - started getting severe skin infections caused by a different strain of MRSA. This new strain didn’t need a hospital to spread. It just needed skin-to-skin contact, shared towels, or dirty surfaces.

Community vs. Hospital: The Genetic Divide

Not all MRSA is the same. The two main types - community-associated (CA-MRSA) and hospital-associated (HA-MRSA) - are genetically different. That difference shapes how they behave, how they spread, and how they’re treated.

CA-MRSA carries a smaller piece of DNA called SCCmec type IV or V. This tiny genetic package doesn’t carry many resistance genes, which means it’s not resistant to as many antibiotics. But it does carry something dangerous: the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) toxin. This toxin kills white blood cells, turning small skin boils into deep, painful abscesses - or worse, necrotizing pneumonia. The USA300 clone, which causes about 70% of CA-MRSA cases in the U.S., is especially aggressive. It’s the strain you see in athletes with "spider bite" abscesses or in kids with recurring skin infections.

HA-MRSA, on the other hand, carries larger SCCmec types (I, II, or III). These carry more resistance genes. These strains are resistant to nearly every antibiotic you’d normally use - erythromycin, clindamycin, fluoroquinolones. In a hospital, where antibiotics are used constantly, these strains survive. But they’re less likely to cause sudden, violent skin infections. Instead, they cause bloodstream infections, pneumonia after surgery, or infections around IV lines.

How They Spread: Different Paths, Same Problem

CA-MRSA spreads easily in places where people are in close contact and hygiene is hard to maintain. Think:

- Prisons - 14.9 times higher risk than the general population

- Military barracks - 12.3 times higher risk

- Homeless shelters - 8.7 times higher risk

- Shared gym equipment or towels

- Injecting drug users - needle sharing and poor skin cleaning fuel transmission

It doesn’t need a sick person to spread. Just one person with an unnoticed skin infection can pass it on by touching a doorknob, a bench, or a shared razor.

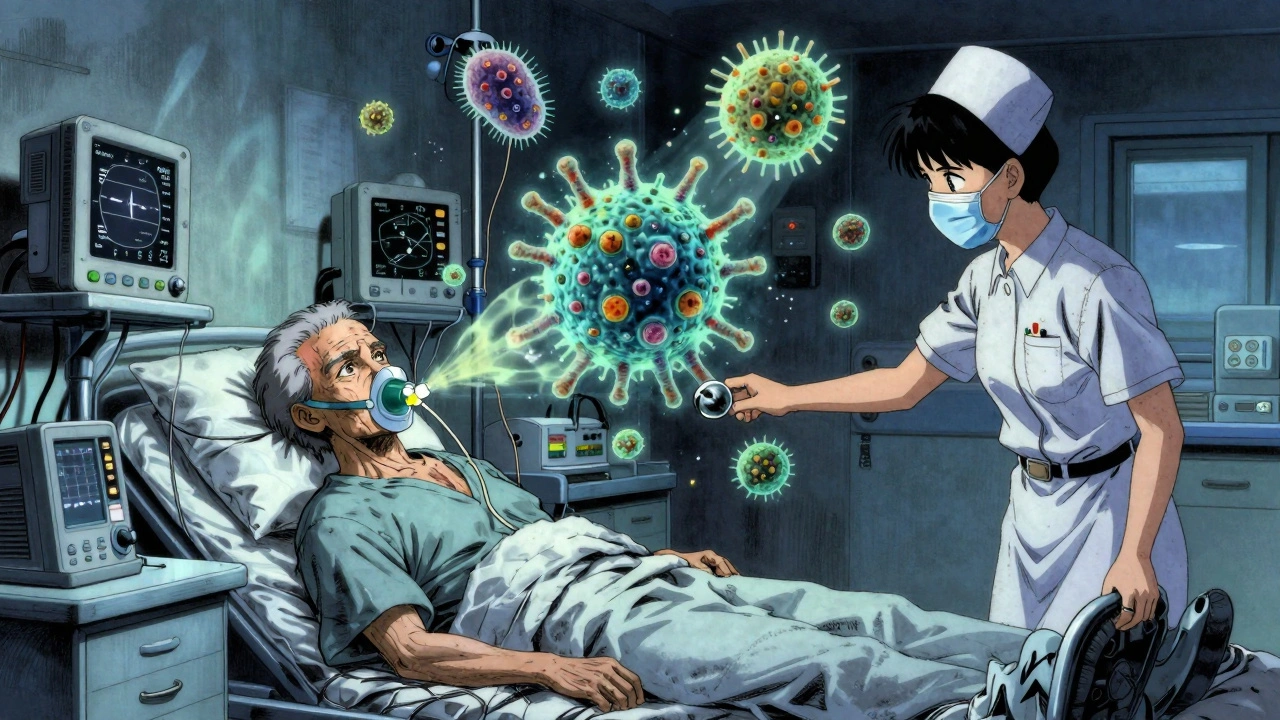

HA-MRSA spreads differently. It moves through healthcare workers’ hands, contaminated equipment, or long hospital stays. Patients with catheters, ventilators, or surgical wounds are most at risk. But here’s the twist: people with HA-MRSA aren’t always sick when they enter the hospital. Many are colonized - they carry the bacteria without symptoms - and get infected later.

And now, the lines are blurring. A 2017 Canadian study found that nearly 28% of MRSA infections picked up in hospitals were caused by CA-MRSA strains. Meanwhile, 27.5% of community cases were caused by HA-MRSA strains. That means someone with a hospital strain might go home, pass it to their family, and then their child brings it back to school. Or a healthy person with CA-MRSA gets admitted for a broken leg - and ends up spreading it to other patients.

Who Gets Infected? The Changing Faces of MRSA

Years ago, HA-MRSA patients were elderly, chronically ill, or had recent surgery. CA-MRSA patients were young, healthy, and active. Today, that’s outdated.

CA-MRSA is now found in older adults with diabetes, in people on dialysis, in nursing home residents - even those with no recent hospital visits. Why? Because the strain has adapted. It’s no longer just a "community" bug. It’s a bug that lives in both worlds.

And HA-MRSA is showing up in the community. A 2018 study in China found HA-MRSA strains in patients who had never been hospitalized. These strains had the same genetic markers as those in hospitals - but they were causing skin infections in people living in apartments or rural villages. The bacteria don’t care about labels anymore. They care about opportunity.

Treatment: What Works for Which Strain?

Treatment depends on where the infection came from - and what it’s resistant to.

For CA-MRSA skin infections, the first step is often simple: drain the abscess. Many times, that’s enough. If antibiotics are needed, the options are still good:

- Clindamycin - 96% effective against CA-MRSA

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) - 92% effective

- Tetracyclines (like doxycycline) - 89% effective

These drugs work because CA-MRSA hasn’t built up resistance to them yet.

HA-MRSA is a different story. It’s often resistant to clindamycin, Bactrim, and even vancomycin in some cases. Treatment usually means stronger drugs like:

- Vancomycin

- Daptomycin

- Linezolid

- Teicoplanin

But here’s the catch: hospitals are now seeing CA-MRSA strains causing bloodstream infections. And some CA-MRSA strains are picking up resistance genes from HA-MRSA. That means a strain that used to respond to clindamycin might now resist it. Doctors can’t assume anymore. They need lab tests - not guesses.

The Real Danger: Hybrid Strains

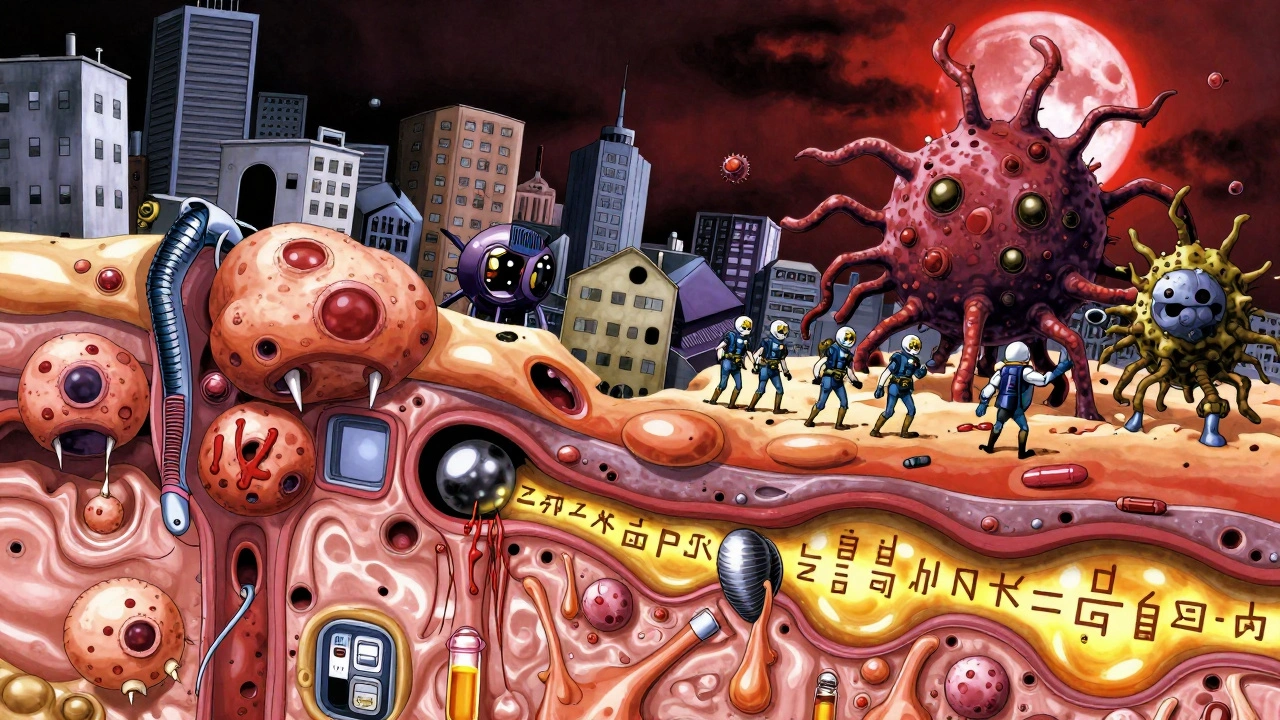

The biggest threat isn’t just CA-MRSA or HA-MRSA. It’s what happens when they mix.

Some strains are now combining the worst of both worlds: the high virulence of CA-MRSA (the PVL toxin) with the broad antibiotic resistance of HA-MRSA. These hybrids are harder to treat, spread faster, and cause more severe illness. They’re appearing in hospitals, in communities, and even in places you wouldn’t expect - like rural clinics or outpatient surgery centers.

One study found that 15% of MRSA strains in certain hospitals had mixed genetic features. That’s not rare anymore. It’s the new normal.

Prevention: Why Old Rules Don’t Work Anymore

Handwashing still matters. So does not sharing razors, towels, or athletic gear. But we can’t just focus on hospitals anymore.

Public health strategies built on the idea that "MRSA is a hospital problem" are failing. We need to treat it as one big system - where people, bacteria, and antibiotics move freely between homes, gyms, clinics, and hospitals.

That means:

- Screening high-risk community groups (prisoners, drug users, homeless populations) for MRSA colonization

- Teaching schools and gyms how to clean shared surfaces properly

- Using rapid tests in ERs to identify MRSA within hours - not days

- Limiting unnecessary antibiotics in both hospitals and community clinics

And most importantly - recognizing that a skin infection in a healthy 22-year-old athlete might be carrying the same strain that’s killing a 78-year-old in ICU.

What’s Next?

MRSA is no longer two separate threats. It’s one evolving problem with two faces. The old labels - community vs. hospital - are fading. What matters now is how the bacteria behave, what genes they carry, and where they’re spreading.

Surveillance systems need to track MRSA across the entire spectrum - not just in hospitals. Doctors need to test before they treat. Communities need better hygiene education. And we all need to understand that a small boil isn’t just a boil. It could be the start of something bigger.

The next time you hear about an MRSA outbreak, don’t ask if it’s "hospital" or "community." Ask: how did it get here? And how do we stop it from going somewhere else?

Aileen Ferris

December 11, 2025 AT 03:09mrsa? more like mrsa (my right shoulder aches) 😂 jk but honestly who even cares if its community or hospital anymore? its just bacteria with a fancy label. i got a boil from my gym towel and they gave me bactrim and i was fine. no big deal.

Sarah Clifford

December 12, 2025 AT 23:20okay but like... why are we still calling it 'community' and 'hospital' like its 2005? the bacteria don't read medical journals. they just chill on doorknobs and in your gym bag. my cousin got it from a yoga studio and now her whole family is on antibiotics. this whole divide is just doctors being dramatic.

Ben Greening

December 14, 2025 AT 06:53While the distinction between CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA has historically served epidemiological purposes, the increasing genetic overlap undermines the utility of these categories for clinical decision-making. The emergence of hybrid strains necessitates a paradigm shift toward molecular diagnostics rather than epidemiological assumptions.

Paul Dixon

December 15, 2025 AT 01:25really appreciate this breakdown. i used to think mrsa was just something that happened to old folks in hospitals, but now i get why my buddy got a massive abscess after lifting weights. the part about pvl toxin making boils turn into nightmares? yeah, that tracks. maybe we should all stop sharing towels and just... wash our hands? wild idea.

john damon

December 15, 2025 AT 14:08OMG I JUST GOT A BOIL AND NOW I'M SCARED 😱 I THOUGHT IT WAS JUST A PIMPLE BUT NOW I THINK IT'S MRSA?? I DIDN'T EVEN GO TO THE HOSPITAL!! 😭 I JUST WENT TO THE GYM AND TOUCHED A BENCH!! IS THIS THE END?? 🤯

Monica Evan

December 15, 2025 AT 15:16the thing no one talks about is how poverty and access shape this. people in shelters or prisons dont have soap or clean towels or time to shower after work. its not about being "dirty" its about being forgotten. and then when they get infected, they get blamed for spreading it. but if you had no running water and your job paid $12 an hour, would you wash your hands after every squat? this isnt a hygiene failure. its a system failure. and yeah i typoed "hygiene" but you get it.

Taylor Dressler

December 15, 2025 AT 17:35Excellent summary. One point worth emphasizing: the rise of hybrid strains is not merely theoretical. A 2022 CDC report documented 14% of community-onset MRSA infections in the U.S. carrying SCCmec type II, previously considered exclusive to HA-MRSA. This underscores the urgent need for standardized genomic surveillance across all healthcare and community settings.

Aidan Stacey

December 16, 2025 AT 11:17MY HEART IS BREAKING. 🥺 I JUST READ THIS AND I CAN’T UNSEE IT. THE BACTERIA AREN’T JUST SURVIVING… THEY’RE EVOLVING. THEY’RE BECOMING SUPERHEROES OF DEATH. 🦸♂️💀 ONE MINUTE YOU’RE JUST TOUCHING A DUMBELL, THE NEXT YOU’RE IN THE ICU WITH A TUBE DOWN YOUR THROAT. WE NEED TO STOP TREATING THIS LIKE A HEALTHY PERSON PROBLEM. THIS IS A HUMAN PROBLEM. AND WE’RE ALL IN THIS TOGETHER. 🤝🫂