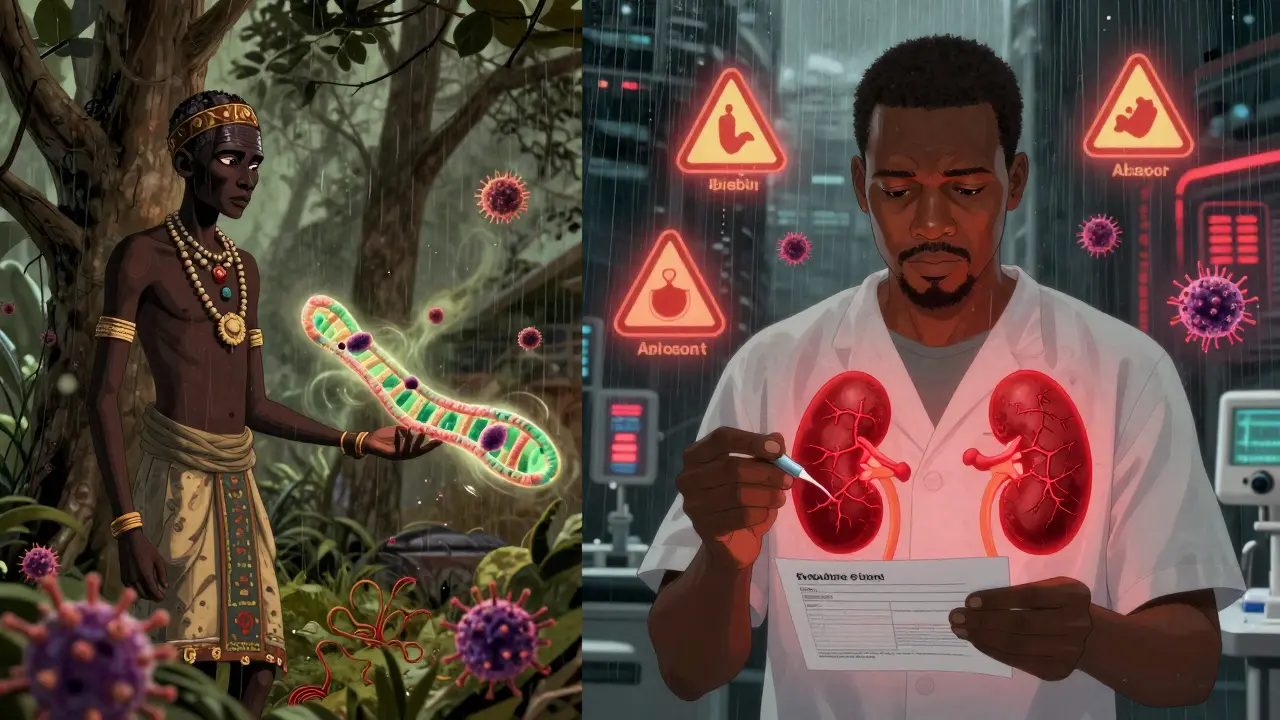

When it comes to kidney disease, not everyone faces the same risk. For people with recent African ancestry, a single gene variant can dramatically raise the chance of kidney failure - not because of lifestyle, not because of diet, but because of something written in their DNA. This isn’t a rare condition. It’s one of the most powerful genetic risk factors ever found for a common disease. And it explains why Black Americans are three to four times more likely to end up on dialysis than white Americans. The culprit? APOL1.

What Is APOL1, and Why Does It Matter?

APOL1 stands for apolipoprotein L1. It’s a gene that makes a protein involved in your immune system. In West Africa, thousands of years ago, certain changes in this gene - called G1 and G2 variants - gave people a survival edge. These variants helped kill a deadly parasite called Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, which causes African sleeping sickness. That advantage meant people with these variants were more likely to survive, have children, and pass the genes on. Over time, these variants became common in populations across West and Central Africa.

But here’s the twist: the same change that protected against a deadly parasite now increases the risk of kidney disease. When these variants are present in two copies - either G1/G1, G2/G2, or one of each (G1/G2) - they start damaging kidney cells. This isn’t a guess. Studies show that nearly 70% of the extra kidney disease risk seen in people of African descent comes from these APOL1 variants.

Who Carries the High-Risk Genotype?

About 13% of African Americans carry two copies of these risky variants. That might sound low, but here’s the real impact: among African Americans with non-diabetic kidney disease, more than half - about 50% - have this high-risk genotype. In fact, nearly half of all end-stage kidney disease cases in Black people with HIV are tied directly to APOL1. That’s not coincidence. That’s biology.

These variants are almost never found in people of European, Asian, or Indigenous American ancestry. But in West Africa, up to 30% of people carry at least one copy. That’s why the risk is tied to ancestry, not race. Race is a social idea. Ancestry is genetic history. And APOL1 is a clear example of why we need to stop using race as a medical shortcut.

It’s Not a Guarantee - But It’s a Warning

Here’s something most people don’t realize: most people with two risky APOL1 variants never develop kidney disease. About 80 to 85% of them keep healthy kidneys their whole lives. So what triggers the damage? Something else - what researchers call a “second hit.”

Common triggers include:

- HIV infection (especially before treatment)

- High blood pressure

- Obesity

- Chronic viral infections

- Use of certain medications like NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen)

That’s why someone with the high-risk genotype might live without symptoms until they get sick with a virus or start gaining weight. The gene sets the stage. The environment pulls the trigger.

What Kidney Diseases Are Linked to APOL1?

APOL1 doesn’t cause just one type of kidney damage. It’s tied to several serious conditions:

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) - a scarring disease that destroys the kidney’s filtering units

- Collapsing glomerulopathy - often seen in people with HIV, but also in others with APOL1 risk

- Arterionephrosclerosis - high blood pressure damage to the kidneys, made worse by APOL1

- HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) - once a leading cause of kidney failure in Black Americans, now much rarer thanks to antiviral drugs, but still strongly tied to APOL1

These aren’t random diseases. They’re all forms of kidney damage that start in the glomeruli - the tiny filters that remove waste from blood. When APOL1 variants go rogue, they punch holes in these filters. The result? Protein leaks into urine, kidneys lose function, and eventually, dialysis or transplant becomes necessary.

Testing for APOL1: Who Should Get It?

Genetic testing for APOL1 became available in 2016. Today, companies like Invitae and Fulgent Genetics offer it for $250 to $450 out-of-pocket. Insurance doesn’t always cover it - yet.

The American Society of Nephrology recommends testing in three situations:

- If you’re of African ancestry and have kidney disease without diabetes or high blood pressure as the clear cause

- If you’re considering being a living kidney donor and have African ancestry

- If you have HIV and kidney damage - even if your HIV is well-controlled

For donors, this is critical. A person with two risky APOL1 variants who donates a kidney puts themselves at higher risk of kidney failure later in life. Testing protects both the donor and the recipient.

What Happens After a Positive Result?

A positive test doesn’t mean you’re doomed. It means you need to be smarter about your health.

Doctors now recommend:

- Annual urine tests to check for protein (albumin-to-creatinine ratio)

- Regular blood pressure checks - keep it under 130/80

- Avoid NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen

- Maintain a healthy weight

- Control blood sugar if you have prediabetes or diabetes

- Get vaccinated against viruses like hepatitis and HIV

One patient, Emani, found out she had the high-risk genotype before any damage showed up. She changed her diet, started exercising, and began regular monitoring. Five years later, her kidney function is still normal. Knowledge gave her control.

The Bigger Picture: Race, Genetics, and Justice

For years, doctors used race as a proxy for kidney function. They adjusted eGFR (estimated glomerular filtration rate) formulas to say Black people had “better” kidney function - even if their numbers were the same as white patients. That meant Black patients were often delayed for transplants or denied care.

APOL1 research changed that. In 2022, the American Medical Association officially urged doctors to stop using race-based kidney estimates. Why? Because APOL1 shows that what looks like a racial difference is actually a genetic one. A Black person with no APOL1 risk might have the same kidney function as a white person. A white person with APOL1 risk? Extremely rare.

But here’s the danger: if we oversimplify, we risk blaming biology instead of addressing systemic issues. People with APOL1 risk often face delays in diagnosis, dismissal of symptoms, or lack of access to specialists. One survey found 42% of patients had their kidney problems written off as “just high blood pressure” before genetic testing.

What’s Coming Next?

The science is moving fast. In October 2023, Vertex Pharmaceuticals reported that its APOL1 inhibitor drug, VX-147, reduced protein in urine by 37% in just 13 weeks. That’s huge. Protein in urine is a sign of kidney damage. Less protein means slower decline.

The NIH is launching a 10-year study tracking 5,000 people with high-risk APOL1 genotypes. The goal? To predict who will get sick - and why. Researchers are also building tools to combine APOL1 status with blood pressure, weight, and viral history to give personalized risk scores.

By 2035, experts estimate APOL1-targeted treatments could reduce kidney failure rates in African ancestry populations by 25 to 35%. But that won’t happen unless access improves. Right now, only 12% of low- and middle-income countries offer APOL1 testing. The science is here. The equity isn’t.

Key Takeaways

- APOL1 genetic variants explain about 70% of the excess kidney disease risk in people with recent African ancestry.

- Two copies of G1 or G2 variants (homozygous or compound heterozygous) are needed for high risk.

- Most carriers (80-85%) never develop kidney disease - other factors like HIV, high blood pressure, or obesity trigger damage.

- Testing is available and recommended for those with unexplained kidney disease, HIV, or who are considering kidney donation.

- Managing blood pressure, avoiding NSAIDs, and regular urine tests can delay or prevent kidney damage.

Can I get tested for APOL1 if I’m not African American?

Testing is primarily useful for people with recent African ancestry, since the high-risk variants are extremely rare in other populations. If you’re not of African descent, the chance of carrying these variants is less than 0.1%. Testing is not recommended unless there’s a strong family history of kidney disease and a known ancestral link to West Africa.

Does having APOL1 risk mean I’ll definitely get kidney failure?

No. Only about 15-20% of people with two high-risk APOL1 variants develop kidney disease in their lifetime. Most never do. But if you have this genotype, you’re at much higher risk than someone without it - especially if you have other health issues like high blood pressure or HIV. The key is early monitoring and prevention.

Is APOL1 testing covered by insurance?

Coverage is inconsistent. Some insurers cover it if you have unexplained kidney disease or are being evaluated as a living donor. Others don’t. The cost without insurance is $250-$450. If you’re a candidate for testing, ask your nephrologist to help you appeal or find financial assistance programs through organizations like the American Kidney Fund.

Can I pass APOL1 risk to my children?

Yes. APOL1 risk follows a recessive pattern. If you have one risky variant, your children could inherit it - but they’d need two copies (one from each parent) to be at high risk. If both parents carry one variant, there’s a 25% chance their child will have two. Genetic counseling is recommended before having children if you know you carry the high-risk genotype.

Why is APOL1 research important for health equity?

APOL1 proves that health disparities aren’t about race - they’re about ancestry and biology. Using race as a medical proxy has led to delayed care for Black patients. APOL1 testing shifts the focus from skin color to actual genetic risk. This allows for fairer, more accurate diagnosis and treatment. It’s a step toward precision medicine that doesn’t rely on stereotypes.

What You Can Do Now

If you’re of African ancestry and have kidney disease without clear causes like diabetes or high blood pressure - get tested. If you’re healthy but have a family history of kidney failure - talk to your doctor. If you’re thinking about donating a kidney - insist on APOL1 screening.

Knowledge isn’t just power. For people with APOL1 risk, it’s the difference between losing a kidney and keeping one - for life.

Ernie Simsek

February 12, 2026 AT 15:54Reggie McIntyre

February 14, 2026 AT 10:09Ojus Save

February 15, 2026 AT 11:33Jack Havard

February 17, 2026 AT 08:22Stacie Willhite

February 18, 2026 AT 19:03Jason Pascoe

February 19, 2026 AT 12:36Sonja Stoces

February 21, 2026 AT 11:10Annie Joyce

February 21, 2026 AT 23:40Rob Turner

February 23, 2026 AT 00:51Luke Trouten

February 23, 2026 AT 03:08Gabriella Adams

February 23, 2026 AT 21:53Jonathan Noe

February 24, 2026 AT 16:06