When your liver fails, there’s no backup system. No reset button. No pill that can fix it. For thousands of people each year, liver transplantation is the only real chance to survive. It’s not a simple operation. It’s not a quick fix. But for many, it’s the difference between a death sentence and a second life.

Who Gets a Liver Transplant?

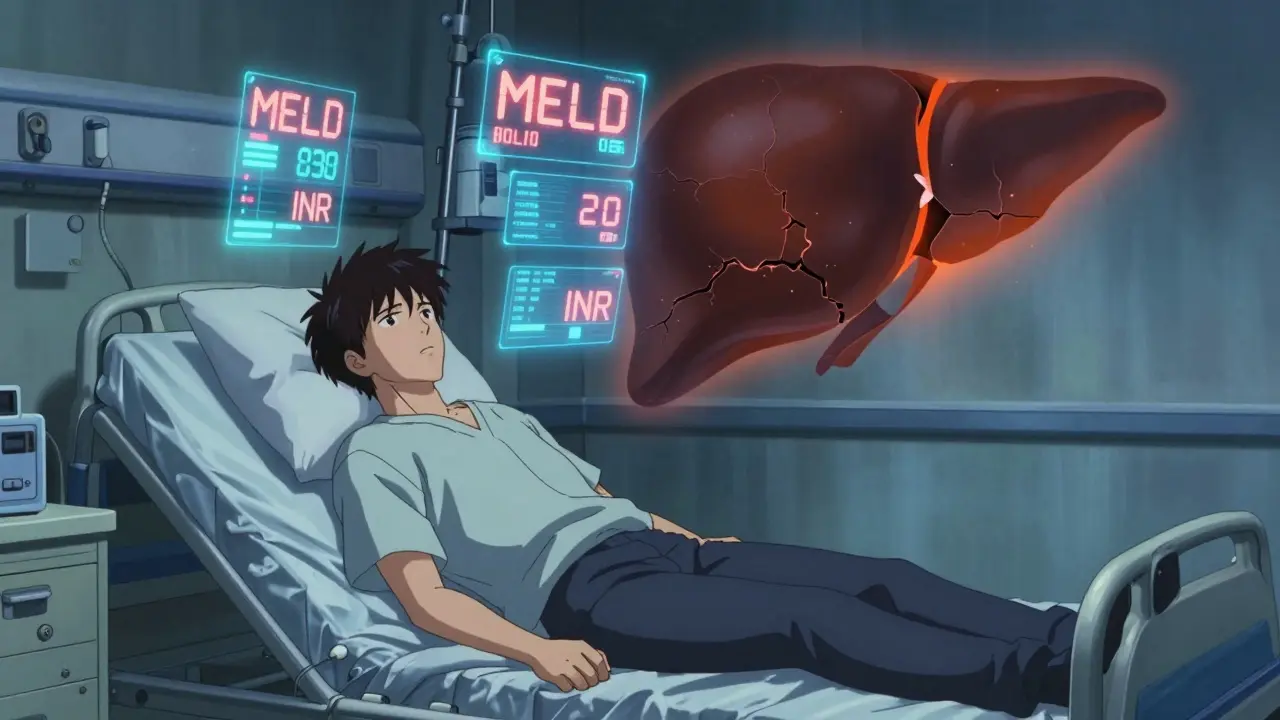

Not everyone with liver disease qualifies. The decision isn’t based on how sick you feel-it’s based on hard numbers and strict rules. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease, or MELD score, is the key. It’s calculated using three blood tests: bilirubin, creatinine, and INR. The score ranges from 6 to 40. A higher score means you’re sicker and higher on the waiting list. Someone with a MELD of 35 is more likely to get a liver than someone with a MELD of 15-even if the second person feels worse. But numbers alone don’t decide everything. You also need to pass a full psychosocial review. Do you have stable housing? A support system? Can you take medications exactly as prescribed? If you’ve struggled with alcohol or drugs, most centers require at least six months of sobriety. Some centers are starting to question this rule. A 2023 study from Yale found no big difference in survival between patients who stopped drinking for three months versus six. But many programs still stick to the six-month rule-especially if your liver damage came from alcohol. There are also hard no’s. If you have cancer that’s spread beyond your liver, you won’t qualify. If you’re actively using drugs or alcohol, you’re off the list. Same if you have other life-threatening conditions like advanced heart or lung disease. Even if your liver is failing, those other problems can make the transplant too risky. For liver cancer patients, the rules are even tighter. You must meet the Milan criteria: one tumor under 5 cm, or up to three tumors under 3 cm, with no spread to blood vessels. If your tumor is bigger or your alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) blood marker is above 1,000 and doesn’t drop after treatment, you’re typically not eligible unless your case gets special review.The Surgery: What Happens During a Liver Transplant

The surgery itself is long-anywhere from six to twelve hours. It’s done in three main phases. First, the surgeon removes your damaged liver (hepatectomy). Then comes the anhepatic phase-when you have no liver at all. Your body survives on machines and careful fluid management. Finally, the new liver is put in and connected to your blood vessels and bile ducts. Most transplants use the “piggyback” technique. That means the surgeon keeps your inferior vena cava-the big vein that carries blood back to your heart-intact. This reduces blood loss and makes recovery smoother. About 85% of transplants in the U.S. use this method. There are two types of donors: deceased and living. Most livers come from people who have died and donated their organs. But living donor transplants are growing. A healthy person-usually a family member-can donate part of their liver. The liver regrows in both the donor and the recipient. For adults, surgeons typically remove about 60% of the donor’s right lobe. For children, they take the left lateral segment. Donors must be between 18 and 55, have a BMI under 30, and be free of liver, heart, or kidney disease. They must also be mentally and emotionally prepared. The donor’s remaining liver must be at least 35% of the original volume to ensure safe recovery. The graft-to-recipient weight ratio must be at least 0.8% to make sure the new liver is big enough to work properly. Living donor transplants cut waiting time dramatically. While someone on the deceased donor list might wait a year or more, a living donor transplant can happen in as little as three months. But it’s not risk-free. Donors face a 0.2% chance of death and a 20-30% chance of complications like bile leaks or infections.Immunosuppression: Keeping Your Body from Rejecting the New Liver

Your body sees the new liver as an invader. Left unchecked, your immune system will attack it. That’s why you need immunosuppressants-for life. The standard starting dose is a triple combo: tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. Tacrolimus is the backbone. Doctors monitor your blood levels closely. In the first year, they want you between 5 and 10 ng/mL. After that, they lower it to 4-8 ng/mL to reduce side effects. Prednisone, a steroid, used to be a must. But now, about 45% of U.S. transplant centers are moving away from it. They start you on it, then taper it out by the third month. Why? Because steroids raise your risk of diabetes, weight gain, and bone loss. Removing them cuts diabetes risk from 28% to 17%. Mycophenolate helps prevent rejection but can cause nausea, diarrhea, or low blood counts. If you get rejection-a common early problem-your team might bump up your tacrolimus dose or add sirolimus. Long-term side effects are real. After five years, 35% of patients have kidney damage from tacrolimus. One in four develop diabetes. One in five get shaky hands or memory issues. Mycophenolate causes stomach problems in 30% of people and lowers white blood cells in 10%. That’s why regular blood tests are non-negotiable.

Recovery and Lifelong Care

You’ll be in the ICU for 5 to 7 days after surgery. Total hospital stay is usually two weeks. But recovery doesn’t end there. You’ll need weekly blood tests for three months, then every two weeks until six months, then monthly for a year. After that, you’ll still need tests every three months. Medication costs are steep-$25,000 to $30,000 a year, just for the pills. Insurance doesn’t always cover everything. Many patients struggle to afford their prescriptions. Some centers have pharmacists on staff just to help with this. You also need to learn how to spot trouble. A fever over 100.4°F, yellow skin, dark urine, or sudden fatigue could mean rejection or infection. Don’t wait. Call your team immediately. Infection risk stays high for the first year. You’ll need to avoid crowds, raw foods, and sick people. Vaccines are critical-flu, pneumonia, hepatitis A and B-but you can’t get live vaccines after transplant.What’s Changing in Liver Transplantation?

The field is evolving fast. New tech is helping. The FDA approved a portable liver perfusion device in 2023 that keeps donor livers alive longer-24 hours instead of 12. That means more organs can be used, especially from donors who died after their heart stopped (DCD livers). These livers used to have higher complication rates, but with perfusion, biliary problems dropped from 25% to 18%. Guidelines are also changing. The AASLD is expanding living donor criteria to include people with controlled high blood pressure and BMI up to 32. Some centers are even considering donors over 55 if their liver looks healthy. There’s also progress on tolerance. At the University of Chicago, 25% of kids who got liver transplants were able to stop all immunosuppression by age five. They used a therapy that boosts regulatory T-cells-cells that teach the immune system to accept the new liver. If this works in adults, it could change everything. Geographic inequality is still a problem. If you live in California, you might wait 18 months for a liver. In the Midwest, it’s eight months. Same MELD score. Same illness. Different odds. And then there’s equity. In British Columbia, they changed their rules in late 2025 to better support Indigenous patients. They now include cultural support teams in evaluations and adjust sobriety requirements based on community norms-not just clinical ones.

Real Stories, Real Challenges

One Reddit user wrote in November 2023: “I was told I needed six months of sobriety. I did it. Then they said my insurance denied my pre-transplant workup. I lost my job. I lost my home. I lost my chance.” That story isn’t rare. One in three transplant candidates report being denied coverage for necessary tests. But there are wins too. A 58-year-old woman in Ontario donated part of her liver in March 2023. She was older than the standard limit, but her liver was perfect. Her recipient is doing great. The transplant team said her anatomy was exceptional. At UCSF, a patient credited their social worker with getting them approved. “They helped me find housing and arranged rides to every appointment. I wouldn’t be here without them.”What’s Next?

Artificial livers? They’re still in the lab. No device has kept someone alive for more than 30 days without a transplant. So for now, the only cure remains a healthy donor liver. The future of liver transplantation isn’t just about better surgery. It’s about better access. Better support. Better understanding of who can be a donor and who can be a recipient. It’s about treating the whole person-not just the failing organ. If you or someone you know is facing end-stage liver disease, the path isn’t easy. But it’s possible. And with every new guideline, every new device, every story of survival, it’s getting a little less impossible.Can you live a normal life after a liver transplant?

Yes, most people return to normal activities within 6 to 12 months. Many go back to work, travel, exercise, and even have children. But you’ll always need to take immunosuppressants, attend regular checkups, and avoid infections. Quality of life improves dramatically, but it requires lifelong discipline.

How long does a transplanted liver last?

About 70% of transplanted livers are still working five years after surgery. For those who survive the first year, the average graft survival is 15 to 20 years. Some last 30 years or more. Long-term success depends on medication adherence, avoiding alcohol, managing weight, and controlling conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure.

Can you drink alcohol after a liver transplant?

No. Even if your original liver disease wasn’t caused by alcohol, drinking after transplant can damage your new liver. Alcohol increases rejection risk, worsens side effects from immunosuppressants, and raises your chance of liver cancer. Most transplant centers strictly prohibit alcohol for life.

What if I can’t afford my transplant medications?

Many transplant centers have financial counselors who help patients apply for patient assistance programs, Medicaid, or drug manufacturer discounts. Some nonprofits offer grants for medication costs. Never stop taking your pills because of cost-talk to your team. There are options, but you need to ask early.

Are living donors at risk for long-term health problems?

Most donors recover fully and live normal, healthy lives. Long-term studies show no increased risk of liver failure, cancer, or reduced lifespan. However, about 1 in 5 donors experience complications like bile leaks or hernias in the first few months. The risk of death is very low-0.2%-but real. Donors are screened very carefully to minimize risk.

Why do some people wait longer than others for a liver?

It’s mostly about location and urgency. Your MELD score determines priority, but where you live affects how many donors are available. In regions with fewer donors, like California, wait times are longer. Also, children and certain rare blood types may wait longer due to organ size and compatibility issues. The system tries to be fair, but geography still plays a big role.

josue robert figueroa salazar

December 26, 2025 AT 16:16david jackson

December 27, 2025 AT 23:34carissa projo

December 29, 2025 AT 16:47Matthew Ingersoll

December 30, 2025 AT 13:38christian ebongue

January 1, 2026 AT 06:55Joanne Smith

January 1, 2026 AT 16:49Sarah Holmes

January 2, 2026 AT 10:43Jay Ara

January 2, 2026 AT 23:54SHAKTI BHARDWAJ

January 3, 2026 AT 17:27Michael Bond

January 4, 2026 AT 16:35Kuldipsinh Rathod

January 5, 2026 AT 06:22Jody Kennedy

January 5, 2026 AT 21:51